Seth Cooke is one of those people who gives sound art a good name. A rigorous adherence to process enables Cooke to refine ideas around – among other things – place, religion, cartography, climate change and history, and then express them via abstract assemblages of field recordings, processed samples, noise and electronics. The latest of these, ‘The Slip’, a rumination on (I think) the difficulties of mapping, signage on the English motorway system and the orthodoxies of field recording practice, was released last month on Nomad Exquisite.

A parallel performance practice sees him exporting his love of process into a more improvisatory realm through devices such as a kitchen sink-based noise rig or vibration transducer-driven cymbals. His partnership with Dominic Lash has been particularly productive in this respect, with their latest forays captured on the gruelling ‘egregore’ (Intonema, 2017).

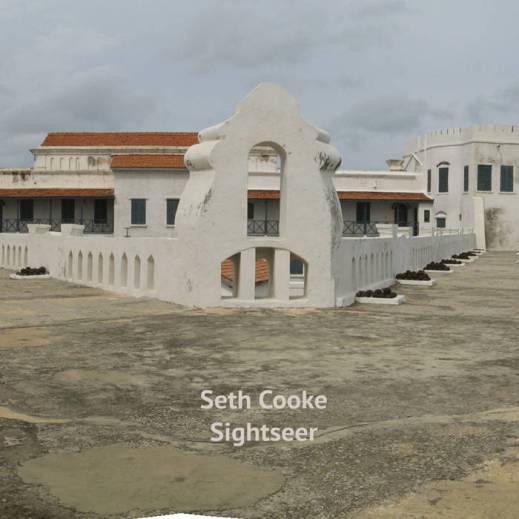

Cooke has a prehistory, as drummer in the bands Hunting Lodge and Defibrillators, but, to be honest, I know very little about that. He first came to my attention in 2014, with his excellent ‘Sightseer’ (Organized Music from Thessaloniki). This evocative mix of muggy hiss, airy field recording, low-key murmurs and eerie calm, as well as being a satisfying listen, served as a perfect entry point into Cooke’s frequently esoteric preoccupations.

His releases have proved essential ever since, and seem to get better every time. Cooke’s discography has gained momentum too, with a rash of solo releases over the past 12 months or so. Hard on the heels of the compelling ‘Triangular Trade’ (Suppedaneum, 2017) was the aggressive splosh of ‘aussen raum’ (Notice Recordings, 2017), the labyrinthine hermeticism of ‘Double B’ (Reading Group, 2018) and the blacktop cacophony of ‘The Slip’ (Nomad Exquisite, 2018). Most recent is ‘Weigh The Word’ (self-released, 2018), which processes cassettes of evangelical Christian ministry through an IBM AI program in a meditation on spirituality, mass communication and technology.

It’s not faint praise to say that a Seth Cooke release wears its learning lightly. However hefty or complex his investigations, the products are never bogged down by them. Instead, ideas, process and outputs coexist in an implicit, mutually-supporting framework. All you have to do is listen.

Unsurprisingly, when the opportunity for an interview with Seth arose, I couldn’t resist the chance to get under the skin of these releases. And if you’re going to do something, you might as well do it right – and so what follows is an epic peregrination through a selection of Cooke’s recorded work. Read on and enjoy. You never know. You might learn something.

+++

1. The centroids cannot hold

We Need No Swords (WNNS): Could you give us a quick run-down of your latest release, ‘The Slip’? Some of the grizzled field recording noises remind me of a motorway heard in the distance – so does the ‘slip’ refer to a slip road? Or is there idea of slippage – whether sonic or semantic slippage … or disjunction / displacement…

Seth Cooke (SC): My titles often have several meanings. Yep, slip road is one reading.

I was partly thinking of motorway incidents. Everyone is born holding a smartphone these days, yet comparatively few people know exactly where they are when they’re on the road. When you’re calling in an emergency the device is probably in your hand or on the dash, which doesn’t necessarily make it easy to use mapping applications. Emergency response will get the mast details for your call when it originated, maybe enough to infer a direction of travel, but no up-to-date location.

So, you have to describe, and that can be fraught. Incorrectly located incidents cause delays in response, there are only so many places that responders can enter and exit the highway. There’s also the risk of follow-on collisions – drivers behind not braking swiftly enough, drivers on the opposite carriageway getting distracted. When they’re reading those situations, control rooms have to make quick decisions – is it one collision or several? On one carriageway or both, and which one? What and where is the event? You get complacent and think that endless concrete track is straightforward, until the ground slips from under your wheels and trying to define ‘place’ ceases to be about academic distinctions.

‘The Slip’ holds other meanings too, and the above is both literal and a metaphor for field recording in general.

WNNS: Does all this relate to the Twitter DM in which you talked about ‘The Slip’ being about “the politics of centroids, mileage calculation and [is] heavily into the weeds on motorway signage conventions”?

SC: The easiest way to unpack this is by talking about the feedback cycle by which human activity produces space, and is in turn produced by space. The definition, position and accessibility of the ‘centre’ is crucial to that.

WNNS: … and perhaps there’s something to do with cartography, or visualization of physical space?

SC: Part of my job is to make maps, and yes, these are core concepts for geospatial analysis. In a less literal sense, I spend a lot of time thinking in terms of where I centre my music and recording, and what is within its bounds, but I rarely nail that down to dots and lines. There’s a bit of work/life balance in play, the interests overlap but the methods are very separate. So this answer is both a detour and sideways hint at how I translate ideas into methods.

In terms of the production of space and how that relates to the centre/centroid question, it’s been a bit of a banner week for these ideas, so I’ll pick three examples. There was the publication of Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler’s outstanding ‘Anatomy of an AI System’, which is a geospatial analysis of the data and resource extraction process behind the Amazon Echo – a single fixed point in your home that relies upon gargantuan and mostly unmappable global material infrastructure.

mmm

Then there’s the YouGov & Sutton Trust Parent Power report, which evidenced wealthy parents buying or renting second homes in the catchment area of desirable schools in order to play the admissions system.

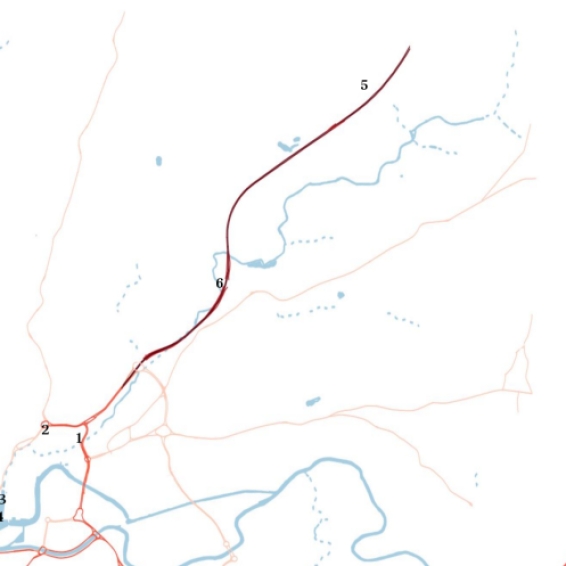

Finally, there’s the controversy surrounding the Boundary Commission’s 2018 Review, which, if adopted, will redraw the electoral map – the methodology for which involved, in part, best-fitting Census Output Areas (COAs) to Westminster Parliamentary Constituencies via the population weighted centroids of each COA. So a centroid is a statistically derived central point, calculated spatially and often weighted by demographic or other factors, but the points and centroids that ‘The Slip’ refers to don’t always meet those criteria.

WNNS: …And centres are always arbitrary, right? The position of the edge, or the centre, depends where you’re standing?

SC: There’s usually a rationale to recover. If you’re in the business of calculating the centre then you’ll have a method, and maybe there are better methods. If you’re calculating a centroid within a geographic boundary, then the geometric method is similar to cutting out the shape via its perimeter line and finding its balance point on a pin. But maybe that’s not a good method if the boundary contains one or more residential centres and you’re trying to fit that geography to another and need to take demographics into account. That’s not arbitrary, it’s about finding the best way of working.

The FiveThirtyEight website’s ‘Atlas of Redistricting’ is a good example. From the abstract for their project: “Each map has a different goal: One is designed to encourage competitive elections, and another to maximize the number of majority-minority districts. See how changes to district boundaries could radically alter the partisan and racial makeup of the U.S. House — without a single voter moving or switching parties.” You can follow their thinking from data to goal to method to map.

There are obvious parallels with field recording – the recording device as a point within the environment, decisions regarding which point in which environment. I generally keep my data concerns at work, and my artistic concerns at home, so decisions about where I centre my music are usually based more on cultural, historic, artistic, conceptual or narrative factors. Sometimes what seems to be the obvious location to visit with microphones will be the least interesting in terms of producing a result that fits your purpose, says something about place or is interesting to listen to. The literal centre is obvious – and often therefore a mistake – while the locus of the idea lies elsewhere. As with mapping, there may be other methods of finding the centre that work better for the story you’re trying to tell or the sound you want to achieve.

nnn

WNNS: In ‘The Slip’, how does the choice and arrangement of the sonic material amplify, echo or embody these ideas you’ve talked about?

SC: You can’t expect me to call an album ‘The Slip’ and be upfront about everything! A few clues – the disconnected stereophony was made on site using a feature of the location; track durations are important; the original field recordings aren’t on the album in any straightforward sense, despite how parts might sound; and there are two versions of the album, one of which won’t be heard by most people.

WNNS: ‘The Slip’ resembles other work (‘Triangular Trade’, etc.) in that there’s accompanying quotes and material side-by-side with the sounds. Could you talk about how the sounds and text fit together?

SC: My releases vary in terms of how they use text, if they use it at all. ‘Triangular Trade’ and ‘The Slip’ use it in quite different ways.

‘Triangular Trade’ was originally commissioned by the Arnolfini for a concert to accompany John Akomfrah’s ‘Vertigo Sea’. The event was pitched to attract an audience that might not be familiar with me or the scenes in which I operate. The film deals with issues of migration and slavery, which holds a significance for Bristol, which still hasn’t reconciled itself to its slaving history. My piece acts as a bridge, dealing with the contested local monuments of that era. So that context demanded some exposition, and as a result the Arnolfini conducted a short interview with me; Madge Dresser (Associate Professor of History at the University of the West of England) spoke at the event; and I drafted some programme notes. A year later I rebuilt the whole composition for the Suppedaneum release, and originally I wasn’t going to provide any text apart from that one sheet featuring the two Akomfrah quotes.

But Joseph (Clayton Mills) suggested making some kind of “quasi-educational” component to accompany the album, and on reflection I agreed. It honoured the spirit of the original commission, that event’s more casual audience, and some of my wider thinking about the themes I was using. It’s a piece that needs to spit the audience back out into the world with something tangible, but without being patronizing. The objective was to offer threads that expanded on the context while simultaneously complicating the work, refusing to lay it all out, not give any easy edges to grasp. So the texts are fragmented, damaged, hidden or collaged – but if you invest time they expand on themes and processes already structured into the music.

mmm

As an aside, 2017 was a strange time to be working on ‘Triangular Trade’. The rebranding of Colston Hall was announced in April, rejecting the name of an historic slave trader. The controversy surrounding the name was already the fulcrum around which the final third of the piece operated. It sounds barely believable, but I was actually feeding the Mahavishnu Orchestra sample back through MACH Acoustics’ impulse response model of Colston Hall when I found out about the rebrand (the first article I read was published at 11:47, when I was on my 147th convolution through the model). Then in August I was making the collage for the inlay while the Unite the Right event was happening in Charlottesville, with Confederate monuments contested across the United States. I decided not to include references to the latter in the art – it just didn’t need spelling out.

I consider ‘Triangular Trade’ to be complete by itself, a standalone piece of music, with the collage and mixtape as separate companion pieces that can also stand alone (the mixtape, in particular, is full of bangers and it deserves its own life quite apart from the composition). Each can be experienced in its own right, without the others, but you can also slot them together in lots of interesting ways, and I’ve made it so that no one will be able to exhaust those connections. No matter how much you pull it apart it always gives more.

mmm

Whereas the text component of ‘The Slip’ doesn’t work like that. The tracks pull the work in one direction, pin it to one set of places, and suggest their own set of concerns – while the quotes pull the work in a different direction, pin it to a different set of places, and suggest different concerns. There is an intersection, but without either one and the resulting tension between them you couldn’t have the whole.

Regarding those accompanying quotes… I feel a lot of empathy for the poor sods who attempted to rationalize London mileages from those contested reference points, a couple of which were based on demolished landmarks that were already fading from the collective memory. If I were a member of Wyld Stallyns in need of an historic lecturer on the subject of geospatial data quality, I’d pick 19th century statistician John Rickman. In some ways ‘The Slip’ is a parallel work to ‘City of London Mirror Displacement’ – picking one location at which to centre a field recording in order to disrupt another location, that second location being London in both cases. I don’t need to go to London again in order to generate yet more bloody field recordings of the place. If the M25 bounds the UK’s navel then we already spend too much time and energy gazing that way.

But the ‘The Slip’ is maybe the inverse of ‘City of London Mirror Displacement’ – the earlier piece is about annihilation fantasies; this is more about the inescapability of London’s gravity well. All of this is stupidly niche, to the point at which I really don’t know who this new record is for.

If you’re going to use text, you need to be clear what your objective is. Does it leave room for people to establish their own relationship with a work? Misleading or complicating the material, or situating the work somewhere between text, music and album art, are usually better approaches than explaining it. Is the text part of the piece, or is it just the equivalent of notes on a gallery wall? I’ve been close enough the genesis of enough field recording releases to have heard, more than enough times, “X will be supplying liner notes”. As though it was just the default position to include text, and usually that text just defaults to exposition. If they feel the discourse is lacking, while also being the ones picking up the slack, then maybe there’s some learning in that.

2. Flow my tears, the Thames Barrier said

WNNS: Tell me more about ‘City of London Mirror Displacement’ and annihilation fantasies.

SC: ‘City of London Mirror Displacement’ was the fulfillment of two briefs. First, there was a half-baked idea back in the old days of the Bang the Bore forum to make some kind of collaborative work exploring the arcane, medieval roots of the City of London Corporation. Second, Bang the Bore was collaborating with the John Hansard Gallery to put on an event to thematically accompany an exhibition of works by Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt. I suppose there was also a third component, which was that Sarah Hughes published an edition of Wolf Notes to complement the concert and exhibition, for which I contributed an article. An article like that isn’t something I’d attempt these days – I’m a poor theorist. But through the process of writing, and making ‘City of London Mirror Displacement’ for the Hansard show, I worked out the basis of the creative approach that’s kept me busy since.

I grew up with fantasies of alternate Londons through children’s books and comics – Michael de Larrabeiti’s ‘Borribles’ trilogy, Grant Morrison’s ‘The Invisibles’, G.K. Chesterton’s ‘Napoleon of Notting Hill’, Neil Gaiman’s ‘Neverwhere’, Alan Moore’s ‘From Hell’. All rooting around in London history and mythology, all churning the same old dirt. So when the City of London Corporation exposés started to surface in the news around the time of Occupy, detailing its ancient and undemocratic hold over Parliament and its obscure titles and rituals, the effect was both sinister and nostalgic, like a Quatermass story. The Bang the Bore webzine had just published Stephen Grasso’s ‘Smoke & Mirrors’ series, which was written prior to Occupy and George Monbiot’s article but trod similar ground. So composing a piece of music around those ideas felt like a dead end, a retread of other people’s relationship with the capital. My relationship was different. I was increasingly weary of London’s self-importance, its cultural and political dominance. I wanted to focus my attention elsewhere.

I spent a lot of time looking at historic and projected maps of the Thames – areas of reclaimed marshland, historic and forecasted floodplains, climate change scenarios, remembering a school trip to the Barrier. It struck me that the River was the lever for outframing London – London couldn’t exist without it, and it may also be undone by it. Beyond that I was stuck. Then one day I woke up with maybe five hours to kill before starting a late shift, and a thought that I couldn’t shift from my head: “Where is the source of the River Thames?” It turned out that the mythological, contested source was in a field in Gloucestershire just down the road. I get a little crazed with compulsions at times like these. I jumped in the car, drove thirty-five miles to Thames Head and had just enough time to record for twenty minutes before having to dash back for work. What you hear on the recording is what happened in its entirety, unedited, no stage-managing.

The composition uses that field recording to frame a short installation piece that’s half mirror box spell, half response to Robert Smithson’s mirror displacements. A pile of shattered mirror fragments stands in for the glass facades of the Square Mile. Low frequency tones are resonated through the pile, vibrating the pieces and re-scattering their reflections, while the shards distort the tones in turn, disfiguring the sound. It’s a kind of cynical, thwarted hex, which ends up embracing neither Smithson nor the magic.

WNNS: ‘The Slip’ is your fourth release of 2018. What the heck’s going on? Are you always this prolific?

I spent years promoting concerts, which used a lot of time and energy. When I slowed the events schedule all that energy became available. Clive (Henry) and I had been programming a series of fairly focused, thematically-driven concerts, so that energy lent itself to creative projects.

We were kicked out of the pub that we’d been using for two years, where we’d been putting on fairly standard noise and improv shows. With the help of Ben Piekut – who at the time was lecturing at the University of Southampton – we were invited to play concerts at the John Hansard Gallery’s former campus site, on the condition that our events were themed around their quarterly exhibitions. So we tackled nuclear energy, error & malfunction, sonification, water, the voice, place & space, collaborative working, all on a shoestring or less. That involved a lot of creative energy – researching the exhibiting artists, finding musicians who either already fit the brief or who could work to a brief. It usually involved coming up with something that I could perform myself, on the cheap, in order to fill out the lineup, as it’s hard to book artists who can do that kind of programming on a budget that’s essentially just our disposable income (we’ve never had direct funding). That experience ruined me for promoting ‘normal’ concerts, but everything I learned along the way contributed to the foundation of the music I make now.

I would have had more material available sooner, but I went through a period where a number of releases stalled due to difficulties with several labels. I’ve got four albums’ worth of unreleased no-input field recording work that I’ll put out as a little box set at some point. But now the dam seems to have burst and things are actually coming out.

3. “Barely even a performance”

WNNS: You’ve described yourself as a ‘process performer’. What does that mean? Where does the interest in process as a compositional tool come from?

My current performance rigs both involve feedback through metal objects, either through cymbals or my waste disposal sink. So I’m mainly referring to feedback processes, but I wanted to leave it a bit more open as I generally like to think procedurally, or in terms of rules, either for direction or to put some distance between myself and my habits.

That’s mainly about performance – whether I’m attempting/failing to be a human mic stand in order to allow cymbal feedback to do its own thing, or whether I’m being more interactive by manipulating feedback through the sink. When I’m composing music at home I also use feedback processes, but they tend to be dictated by the material I’m working with. It’s rare that I encounter feedback that I don’t like – although I’ll probably give it a bit of a rest soon.

WNNS: Does your interest in process give you a fixed methodology for each work? Or is it more flexible?

SC: Every work is taken on its own terms, I’m led by the material. That either gives me a lot of flexibility or none at all. Once I’ve got a sense of the ‘rules’ of my material then the process of realizing it tends to run on rails – but those rails can be very different from project to project. I’m really bloody-minded about sticking to rules once I’ve made them. I always make sure that, whatever smartphone I have, I keep a panel-grab from Frank Miller’s ‘Dark Knight Returns’ in the image gallery. Miller writes a famously fascistic take on Batman. The panel in question has Batman about to face the leader of the Mutant Gang in hand-to-hand combat, turning off the Batmobile’s weapons, providing this as the only explanation: “Can’t give myself a back door, Alfred. Might be tempted to use it.” Although that didn’t work out very well for him, and I often wonder whether I’m being equally idiotic. As idiotic as Batman.

WNNS: But it sounds like you draw a distinction between performance with the rigs, and composition at home, I guess?

SC: Yes, definitely. I draw another distinction between performing with the feedback rigs and performing with a full trap set. I have no interest in free improvisation when drumming, I just want to play rhythms and hit hard. I sometimes play free in ensembles with the sink, but I increasingly have misgivings about it. I think of it a little bit like that classic sample-based hip hop approach that’s getting revived via mixtapes – the whole world of recorded music as a resource, and it all gets crushed into that one conservative form.

Don’t get me wrong, I love hip hop, especially that sound and those eras. But free improvisation is usually similar – the rhetoric is at odds with the results, all the idiosyncrasies of the players get smeared out until the group finds its lowest common denominator, like when [UK musician and TV presenter] Jools Holland’s muso mates jam at the end of the show and default to a twelve bar in E. People talk a lot about endless possibilities but with most free improv you generally know what you’re going to get.

These days I feel more comfortable with the sink when I approach it from noise rather than music. I don’t want to feel as though I’m improvising. And the cymbal feedback is another thing entirely – it’s not improvisation, it’s not composition, it’s just allowing a process to take place. I’ve done shows where I just put the mics on stands and hold a volume control, so it’s barely even a performance.

WNNS: Is it possible to generalize about the relationship between the idea that a work explores and the process you follow to realise that? Does idea shape process or vice versa?

SC: The two feed back into each other. There are processes I’d love to have at my disposal but I don’t have the time or energy to learn. For example, I’d love to have a few data sonification strategies at my disposal, because there’s so much bad sonification around and I’d like to try my hand at getting around the pitfalls. But my priorities are elsewhere, and my processes are dictated by my resources.

An example of how that plays out: for one of my next projects I plan to do some work around online AI content curation. But I haven’t got the coding skills, so my network charting will be a manual process, and rather than directly sonifying the results I’ll be collecting my material through other means. Of course that will be time-consuming in its own right, but it in pragmatic terms it will deliver results that I’m confident will sound good and deliver the right conceptual heft, just using the time and resources that I have. Most of what I do is pretty cheap, in relative terms.

4. Trapped gas, no inputs

WNNS: Can we talk about no-input field recording? Could you tell me a bit more about how you discovered / decided on this technique, given what you have said about exploring what music isn’t being made, etc.?

SC: It was the kind of accident that most people would dismiss. We had just moved to Bristol and my wife, Sara, was looking for work, so we were a new family of three living in Dan Bennett’s spare room. I had just made a website for my own music, collecting up a few odds and sods. I’d been an ensemble player up to that point but was taking those first tentative steps towards believing in my own voice. Those early Hansard shows, plus some solo shows and recording in Leeds, pushed me out the door. So I was at quite an impressionable stage, just starting out and developing what I wanted to do.

Sara had suggested that I make recordings of the sounds of our daughter as she was learning to speak – for family documentation, not for any musical purpose. Our daughter had been talkative that morning, so I made some short recordings, imported the WAVs into a DAW [digital audio workstation], normalized them, and was hit by a wall of noise. It took me a second to realise what I’d done. Most of my recordings were from live shows, which I typically record in four channels. Through force of habit I’d normalized two stereo files, but two of the channels had no mics plugged in.

If I’d been at a different point I might not have listened further. Most of the results were relatively plain, close to white noise, but one of them contained artefacts that surprised me in the low and high frequencies. I still have the recording. Jez French released an excerpt, and part of it wound up on ‘Sightseer’, but I really love the full piece, so it will be released unedited and untreated as one of the four discs in the aforementioned set. I sent the recordings to a few field recordists who had expressed an interest in my early stumbling. Two of them immediately asked to work with the results – leading to my first unhappy collaborative experience. But with the benefit of hindsight I got lucky.

In a nutshell, they worked on the files with a very swift turnaround, submitted their contributions to me, I said I’d get back to them after reviewing the recordings… but before I’d even had a chance to listen they’d submitted it as a finished release to Gruenrekorder, with a crappy title and crappy art. I put my foot down and told them I wouldn’t allow that, and they withdrew the submission. So then I listened, and it seemed clear to me that they’d worked within their existing aesthetic without really considering what my material really was (hence the swift turnaround). It was also a long record, just shy of eighty minutes, with five tracks submitted by one of the parties that were pretty similar to each other. I pitched a new conceptual frame and title for the record that addressed the disconnect between my work and theirs, which to my mind salvaged the record.

I submitted it to a couple of labels, who fed back that it could do with chopping 25 to 30 minutes off the duration. That seemed fair enough to me, but the other two collaborators were unhappy. And one of the labelrunners – who I won’t drag into this by naming – provided what turned out to be the best possible response. I’m paraphrasing from memory, but it was something like: “You’ve produced this no-input material, which calls the whole enterprise of field recording into question, yet you’ve capitulated back into orthodoxy by collaborating with these guys.”

Meanwhile two other projects had been ongoing. Simon Reynell released my first no-input field recording work via my contribution to the Another Timbre online project to release multiple realisations of Manfred Werder’s ‘2005(1)’. To accompany that release I wrote a short paragraph detailing the intersection of my ideas with what I understood of Werder’s. And I was also working on Bang the Bore’s ‘Displacement Activity’ event at the Hansard, the aforementioned show complementing their Smithson & Holt exhibition, which included ‘City of London Mirror Displacement’, a realization of James Saunders’ ‘Location Composite #1’ and my article for Wolf Notes #6. So I had been steadily gathering my thoughts regarding what I wanted to say about ‘place’ and field recording. All of that – combined with the lack of trust, the misgivings about my collaborators’ contributions, their inflexibility over editing, that labelrunner’s observation – came together in my head, and I pulled the plug on the unreleased album.

Two records resulted from that experience – ‘Four No-Input Field Recordings’ was the two-finger salute, and ‘Sightseer’ repurposed the conceptual frame that I’d pitched to salvage the record I ended up ditching. Thinking about it now, “pulling the plug” is a nice, tidy way of encapsulating that whole period.

hhh

WNNS: Why do you think this has proved so fruitful for you (or why has it held your interest for so long)?

SC: I thought about giving it up a while ago, but sometimes when you’re flogging a dead horse it unexpectedly and explosively shits everywhere due to an eruption of trapped gas. There are so many different ways that you can play with that crappy recorder. The four-disc set I’ve got lined up – each one is its own thing, there’s very little crossover of sound or method. There’s some noise, some feedback pieces, some heavily edited tracks in the vein of ‘Sightseer’. The method is versatile, both sonically and conceptually.

In terms of the former – sonic versatility – it’s close enough to coloured noise to be almost as useful. When people think of wideband noise they think of waterfalls or ocean waves, so I’ve done a lot around displaced water or displacement by water (‘Christ of the Abyss’, ‘aussen raum’, ‘Triangular Trade’, tracks on ‘Sightseer’). The BBC Radiophonics Workshop’s old gunfire effects simulator was essentially a white noise generator hooked up to a filter (‘Architectural Model Making’, ‘Double B’); you can use no-input recordings to simulate or augment snare drums, hi-hats, brush rhythms or shakers (‘Double B’); you can use it to make impulse response recordings to model rooms (‘Architectural Model Making’, ‘Triangular Trade’). It’s pretty pliable.

Then there’s the conceptual versatility. On the one hand, the practice is about the recording device as a material, physical object, and the artefacts that it produces as a consequence of a marketplace that causes corners to be cut on build quality in order to drive down cost. I make them using a Zoom H4n, which is so ubiquitous as a cheap four channel recorder for N00Bs that you can use it as a lever to comment on the proliferation of field recordists as a whole. A parallel from photography might be the Pentax K1000, in terms of affordability, ubiquity and association with beginners (although nothing’s built for that kind of longevity these days).

Otherwise, quoting from a letter I wrote to the artist Mike Nelson, no-input field recording “could represent the qualities of a location that can’t be recorded; might suggest erasure or annihilation; foregrounds the presence of the recorder and recordist; might contain distorted, denatured traces of the outside world; could contain introverted, insensible phenomena without any apparent connection to the world; hints at the oceanic; hints at the unconscious; could be used for scrying, or resembles EVP methods; presents the device as a singularity into which the universe is drawn and crushed; could be the act of a stumblebum tourist leaving on the lens cap. One block of sound can stand for all locations, no location, dislocation.” Again, pliable.

bbb

Then there’s the manner in which the sonic and conceptual play together when the material is so narrow, how cathexis operates when you’re funneling all meaning through a single thing, or single class of thing. The works rub up against each other, comment on each other, feed into each other. A listener might conclude that ‘Christ of the Abyss’ is a spiteful little satirical record – so what do they conclude when that material turns up again as ‘Triangular Trade’? Meaning bleeds between the works like signal bleeds between the recorder’s shitty preamps.

I guess finally there’s the name. I chose it because it annoyed me. It still does. In the context of the no-input mixing board it refers to there being no external input, but in concrete, physical terms an output plugged into an input is still an input. And as someone who also works with feedback, when your output feeds your input you have an orchestra. I’d extend this pedantry into a routine but it’s annoying me too much to even type it, and I think we both know where it’s going. Imagine Stewart Lee taking up the baton.

WNNS: Could you tell me about how you use no-input field recordings to critique field recording practice?

Back when I was making ‘Four No-Input Field Recordings’, the questions were pretty fundamental to the practice of field recording. You go somewhere, or at least leave the controlled environment of the studio, you record what’s there. I’m not even going to get into naturalism/antinaturalism, questions around framing or transmitting the recordist’s experience, I’m going to keep things that basic. Unpick it. “You go somewhere” – “somewhere”, literally meaning “approximate” or “unspecified”. How unspecified can you get? “The controlled environment of the studio” – what if the most uncontrollable variables were the devices you brought with you, producing artefacts that most seek to minimise, silence or purchase their way past? “You record what’s there” – what’s omitted? Can a place really be revealed through just a sound recording, even to the recordist?

With ‘Four No-Input Field Recordings’ none of the usual reference points are available. There’s no confirmation or even indication that I went anywhere; no sense of any environment, controlled or otherwise; there’s nothing in the sound to help you locate or position it. There’s no text, every track has the same title, there are no photos. But in other ways the record fits neatly into the tradition of field recordings of quiet sounds, or sounds from places where you can’t put your ears, just applied to the device itself.

But I’d use the past tense. I have less time now to keep track of what people are releasing, so I have decreasing knowledge regarding whether my stuff still functions as a critique.

5. Trace the space of the place

WNNS: Given that no-input field recordings could relate to anywhere, why is place so important to your recorded works? Is that any field recording problematises the idea of place – or is it about destabilising the authority of the recordist?

SC: They’re two separate things. I’m interested in place, period – and no-input field recordings can be one way of exploring that. ‘City of London Mirror Displacement,’ ‘5102’, ‘Architectural Model Making’, my realisation of Michael Pisaro’s ‘Only – Harmony Series #17’ are very much about place but don’t use no-input field recordings at all (although a couple use ideas or methods that share similarities). My plans for the next couple of records deal with place, but they won’t feature no-input recordings – in fact I won’t be making field recordings of any kind. And when I do use no-input, some of the works don’t specify place, but others are extremely specific.

It’s less that I think that any field recording problematises the idea of place, and more that I think much of it misses the idea of place. There’s a lot of engagement with audiophile concerns, equipment, gear, methods. There’s a lot of engagement with going to places that I’m guessing are exotic to the recordist. There’s a lot of engagement with liner notes and accompanying documentation.

But for a form that trades on being about place the most you usually get is microphones taken somewhere – and that’s far from enough for me. So part of what I’ve chosen to do with the no-input method is to claim that “I can say as much or more about place using my undifferentiated slabs of noise as you can with your posh mics, fancy preamps, plane tickets, carbon footprint and gap year – and I can do it in a way that stinks less of expensive collectables, ableism and imperialism.”

WNNS: There seems to be a continuum in your field-recording related work, between works where the place it describes is semi-recognisable – I’m thinking of ‘aussen raum’, ‘Sightseer’, etc – and those where the link is submerged or concealed through the full-on no-input technique (‘Christ of the Abyss’, etc…). Is that dialectic between recognition and ambiguity, or clarity and noise, deliberate?

I do what’s right for the piece, whether that’s dictated by the material, a score or concept. ‘aussen raum’ was about maintaining total obedience to Stefan’s score, while simultaneously bending it to my interests. The instruction ‘several times / between sound and noise’ came to be about the signal-to-noise ratio across different instantiations.

‘Sightseer’ was pretty scrapbooky, but united around the theme of the indifference of the device and the seeming indifference of many recordists. It contrasts what’s going on inside and outside the recorder; sometimes what’s happening inside is more or less identical between different outsides; and sometimes it isn’t, and there’s often little that’s replicable about how that plays out. ‘Christ of the Abyss’ was another record about annihilation – a tide and weather dependent journey to make an audio recording of a cave painting of the Crucifixion that’s at risk of erasure by rising sea levels, that uses both the wrong representational modality and is obliterated by the no-input material anyway… and maybe I didn’t bother going there to make the recording in the first place.

Yes, there’s that aggregate effect. ‘aussen raum’ and ‘Christ of the Abyss’ are in dialogue with each other. You’d be forgiven for thinking that I went to the one place but not the other, and that’s why you think you can hear that place in the former but not the latter. But for the former the river was inaccessible, while the for the latter the cave is only intermittently accessible, and both pieces are about water that can’t be heard due to durational processes that must be represented rather than captured. You could replace parts of ‘aussen raum’ with ‘Christ of the Abyss’ and most listeners wouldn’t be able to tell the difference, and both pieces would still work fine conceptually, even in terms of the relationship between ‘aussen raum’ and its score. That might be a step too far for some people, but I don’t think it’s particularly outlandish. A lot of field recording is interchangeable to my ears, just without the self-awareness. The rhetoric about the uniqueness of each captured moment is overstated. If you’ve been out with mics more than a few times then you generally know more or less what you’re going to get.

That’s one of the many strands that make up ‘5102′. I think if that set of circumstances had happened to most other recordists they’d have built a theology around it, so I punctured that notion there and then, in the moment, in that place.

WNNS: What about techniques and sound palette? There are some commonalities around the techniques you use – field recordings, extreme layering or manipulation of sound, and so on. Are you consciously drawing on a suite of tools, techniques or sounds to deliver the work – or does it just depend on the individual project?

SC: I’m actually at the point at which I want to take things in a different direction. I’ve been working with no-input field recordings for six years now, so it’s time for a break. The next big project will still be location-based, but without me making field recordings of any kind. For that project there are two or three new software-based composition/performance tools that I want to learn, so that will provide some new sounds and textures. That box set of unreleased no-input work will probably represent the last of that way of working, for a while at least (although it’s mostly quite different to what people might associate with my no-input field recording work).

I’m also planning to retire the cymbal feedback rig unless I’m specifically asked to play that kind of set. I’ve been doing it for around four or five years now and that feels like enough. Although that’s complicated by Dom (Lash), who has just switched from double bass to sine waves for our duo, and he understandably wants to go further with that combined with the cymbals. I’m not a dictator so I’ll run with him on that to see if there’s another album there.

In fact, I’m going to cease to work with feedback for the foreseeable, with two exceptions. The first is the aforementioned duo with Dom, depending on how that goes. The other is my waste disposal sink and metal detector rig, which is my main set-up for solo and ensemble live performance. I rebuilt that rig last year but have barely used it outside of playing with Mark Wastell’s ensemble, The Seen. It’s now quite different from the rig I used for ‘PACT’, the first duo album with Dom. It’s much more ‘pure’ – about the qualities of the metal alone, rather than augmented with synth and radio, which were easy performance crutches. The new sink rig deserves to be documented for at least one album, probably solo, although I have plans to make that less straightforward than it sounds.

Given all those self-imposed restrictions and new ways of working, I anticipate that I’ll be editing more and processing less. My reasoning is that it will be fresh territory for me and I’ll want to present it close to as-is, while knowing that some assembly will be required.

6. Shot totems, software baptisms

WNNS: Can we digress to talk about ‘Double B’ – another very involved, rich and complex work. I know there’s some allusion to Mike Nelson’s work in there, as well as a lot more stuff. How does all this fit together? And what’s the significance of the title?

Titles, plural. Imagine a wildcard after the ‘B.’

‘Double B’ draws from four sculptures/land works. The two most important to the piece are Robert Smithson’s ‘Partially Buried Woodshed’ and Mike Nelson’s ‘Triple Bluff Canyon’, which included a rebuild of Smithson’s woodshed. ‘Double B’ is intended as a third woodshed in the series. Smithson’s work was situated at Kent State University and its meaning became altered after the National Guard opened fire on student protesters on 4th May 1970. Nelson runs with that and further alters and recontextualizes the work for his piece at Modern Art Oxford. My concerns are different again to those of both Smithson and Nelson, but the aim was to hold on to their shared thread to retain just enough continuity. I’d recommend to anyone that they invest some time in getting to know both artists and both works.

To a lesser extent, Nancy Holt’s ‘Sun Tunnels’ and Donn Drumm’s ‘Solar Totem #1’ are also important. When I researched the Kent State shootings I discovered that Drumm’s sculpture was hit by a stray shot. The bullet hole, and the title of Drumm’s sculpture, immediately reminded me of the solar alignments of Holt’s iconic ‘Sun Tunnels’ – and of course Smithson was Holt’s partner, and it’s usually her words that are quoted when art historians talk about the transformation of meaning for the woodshed after the Kent State shooting. So you have the woodshed as a constellation of ideas repeating through time and space, the solar systems of Holt’s concrete tunnels, the sunlight through the bullet hole keeping the time.

My woodshed is visible from the M32, Carriageway B side, between Junctions 2 and 1. It’s too close to the motorway to make an effective hideout, but nonetheless that notion is linked in my mind due to the familiar sight of vehicles having been pulled over along that stretch of road. ‘Double B’ is about the spaces in which men become radicalized and the places used by radicalized men – combatants returning from foreign battlefields, white supremacist militias, lone shooters, those who drive cars into crowds or whose suicide involves collateral damage. And it’s about the permeable line we draw between them and us, the point at which the radicalized and the institutions are indistinguishable, and the fog of gang weed that now drifts across those battle lines. Think 14/88 dog whistles in that Department of Homeland Security press release, or the OK symbols in the Jasper PD photograph. A few weeks ago you sent me a link to Richard Cooke’s article, ‘Notes on Some Artefacts’. That piece really nails some of my thinking.

But the album pulls all of that much closer to home. For me, ‘Double B’ is primarily about Brexit catharsis. While I saw the outcome of the vote coming, that did nothing to mitigate the trauma. At the time of the Referendum, I was an analyst in the public sector with a portfolio that included community cohesion issues relating to racial hatred. So I was at some remove, not public-facing, but it was a remove that had me directly involved in measuring the impact of the vote. My wife is mixed race, she was pregnant with our second daughter at the time. We found ourselves, in 2016, having a conversation about the likelihood that our unborn daughter might be able to pass for white, like our eldest. Nancy Holt’s words, describing Smithson’s woodshed – “Really, we had a revolution then. It was the end of one society and the beginning of the next.”

So while the majority of the album was recorded on site at the M32 woodshed, I knew I needed to bring one track into our home. We were converting our attic, putting down boards, turning it into what is now my project space. While clearing out decades of the detritus of previous occupiers, I came across a tattered Tomorrow People novelization that my older brother used to own when we were kids. I thought about makeshift DIY attic hideouts, violent men hiding out amongst their childhood possessions, re-reading pulp sci-fi, long forgotten comic books. I needed to make that link, back to a lone musician holed up in his attic studio plotting his next release.

WNNS: A recent release that I found particularly affecting was ‘Weigh the Word’. How did this project come about?

SC: I’ve been carrying around five or six cassette tapes of Charismatic Evangelical Christian prophetic ministry recordings for around twenty years. I grew up in those kinds of churches and my Dad ran Schools of Prophecy. He must have trained thousands of people worldwide. The tapes were made by people he’d trained, at his conference – although Dad was never present at those sessions himself, because of his rule that he doesn’t prophesy over his own children. I was the subject they were prophesying over, although my voice doesn’t feature on any of the tapes. I’ve come to appreciate that triple absence – I don’t feature, Dad’s not there, and God’s isn’t either, by dint of not existing. Void in Three Persons.

A labelrunner approached me with a very specific pitch – to do something around our shared interests (field recording, magic/religion/psychotherapy, noise) for a 26-minute cassette release, thirteen minutes per side. It coincided with a project I’d been involved with at work, for which I collaborated with a team of IBM interns developing an app that used speech-to-text. One of the things I liked about IBM’s Bluemix online interface was that you could watch the algorithm in progress. It would begin transcribing, then delete text and retranscribe as it gained new context.

That put me in mind of the ministry cassettes, which each had instructions on the inlay that the recipient of the prophecy should transcribe the tapes as part of the process of “weighing the word” in the context of church leadership counsel and consulting scripture. I had already decided that all the sounds on the album (with two exceptions) should be derived from the tapes and the process of digitizing them, so speech-to-text transformations fell in line with that. Essentially using the ‘Guidelines for Interpreting Personal Prophecy’ from the inlay as a text score.

So what you’re hearing is a 2017 IBM English language AI attempting to parse, through a layer of tape hiss, the 20-year old prophecies of a South American woman whose applied theology and techniques are idiosyncratic to say the least (syncretic would be my assessment having experienced her ministry outside these recordings).

WNNS: I’m interested in the personal aspect of this. For one thing, there seems to be very little rancour or bitterness discernable in ‘Weigh The Word’ – which I can’t help feel is a little unusual for people who have experienced very religious upbringings then come out the other side (so to speak). How easy was it to maintain a critical distance?

SC: I was quite selective, which isn’t quite the same as critical distance. I focused on the richest, most complex material to mitigate against anyone – myself included – being able to have an easy experience of the results. In some ways that brought it closer, made it more personal – but not in the sense that it gives much insight into me, which is never something that interests me. It might sound counterintuitive to increase complexity by reducing scope, but I think that it’s easy for a lot of people to resort to their default positions with religious material, especially Christian material, and one reaction against one voice in one place can leak across a whole project.

So while there are other people prophesying on the original tapes, I chose material from the person who was the most skilled, who had the most to say, and who had the most individual ministry. It was a pleasure and an honour to spend time with her voice and thoughts, twenty years later. It was also interesting to hear her work transformed by the AI – at points I jokingly wondered whether it was scanning my directories or using my laptop mic for additional contextual keywords, because it seemed to be talking about my life now, rather than transcribing what she said then. I’m not going to get conspiracy theorist or think magically about that though. (Listen to ‘Weigh the Word’ here.)

It’s also material about which I have to feel some distance, because it’s essentially a room full of people who barely know me telling me what God thinks of me. No matter how interesting I find that one speaker on the tapes, that’s still the case. Since I parted company with the faith, distance and dissociation have been the best tactics on the occasions that I’ve had to venture back into the ministry environment. I remember going to check out one self-styled prophet who had spoken some startlingly hyperbolic stuff over a musician friend who wasn’t a Christian. At the service he singled me out and started prophesying over me, in preference to all the Christians present who had actually responded to his altar call. Perhaps he knew that I was my father’s son. He was clearly cold-reading, he’d got the whole able-bodied segment of the congregation to come forward with his range.

I put myself into a trance that superficially appeared receptive, but my attention was elsewhere, so I have no idea what he said. I was dimly aware that he was having difficulty because he kept moving on and coming back to me, only to again get nothing because I gave him no physiological cues. He approached me after the service, he seemed a little spooked. If I’d reacted against him then… well, many Charismatic Evangelicals have readymade narratives to project onto overt resistance. So distance is generally a useful approach.

I don’t think the woman on the tapes is cold-reading though. Much of her work is done in prayer and meditation before a subject even enters the room. If you listen closely you can hear that she’s working from objects and images, which some people use as a technique to mitigate against unconsciously responding to physiological cues from the subject. So she’s no charlatan, nor is she naïve or without power – but that doesn’t mean that her techniques work as intended or that she receives insight from God. It’s complicated, and I truly hope that complexity comes across to the listener.

These days I don’t describe myself as atheist because it’s too weak a position – you award the theist position primacy by defining yourself in negative against it, and if you had to invent new words to define yourself against every unevidenced position then there’d be no end to it. I can still impress my Catholic mother-in-law by reciting whole passages from the Bible, and I can exclude almost everyone with theological in-jokes, so it wasn’t all wasted. Last week my mother-in-law was commenting on a classroom assistant for whom English wasn’t their first language, for some reason they’d attempted to write “Jesus was clever” on the whiteboard but had ended up writing “Jesus was cleaver.” So of course I responded with Hebrews 4: 12. Sad bastard.

7. The world in an empty vessel

WNNS: Once you look for it, the personal seems to be almost everywhere in your work. On the surface, it is very dispassionate, impersonal. Yet often it is informed by places that have some personal significance, or by very specific iterations of ideas. Is this just how art works, or you do deliberately make space for the personal in your projects?

SC: It’s how it works for me. I do my best to reach for something outside myself, but as you pour yourself into achieving that it inevitably becomes personal. That’s much more interesting to me than artists who play with things that only really have significance to them. I don’t really care about the artist, their life or their history, unless they’re a friend. I care about what they make. So the idea is usually to get outside of myself, but as that’s impossible it’s only ever a technique, a means to approach the project. It’s not true, and the personal leaks back in through the effort, the focus and the failure.

At the moment I’m working on a piece that maps a geographic location as it’s referenced in titles and tags on an online content platform. I’ve adapted the derivé technique of following a stranger around a city, so I’m not using the site as I would use it, and I’ve set some rules that I have to follow to the letter in order to keep things impersonal. It’s thrown up a bunch of stuff that I wouldn’t have otherwise encountered that is enriching the work in really interesting ways. And for the things I went in expecting to find, the story I wanted to tell in the first place that set this for me as the most appropriate method, that’s all there too – but held in a far richer, more robust context, that’s been analytically tested, so I can answer questions that I otherwise couldn’t, which in turn gives me more avenues to develop.

By the time it all becomes music, the listener won’t hear the analysis – they’ll hear the immediacy, the personal, the grit. And it won’t be inert or laid out in every little detail, because the rigour allows the work to spin out in more directions than I can possibly unpack. That’s why I have no problem talking like this about what I do – I can’t explain it away, because I’m barely scratching the surface. You can rip the guts out of the machine but it just keeps on working anyway.

bbb

WNNS: Religion is a very big part of ‘Weigh The Word’. It also crops up in ‘Christ of the Abyss’. Is this coincidence?

SC: ‘Intercession’, ‘City of London Mirror Displacement’, ‘Santa Barbara Christian Field Recording Association’, ‘Weigh the Word’, ‘Christ of the Abyss’ – it’s pretty intentional! ‘Christ of the Abyss’ is probably the most condensed, taking things on a stage from the way I approached Werder’s ‘2005(1)’. The triple riff on anthropocentrism – the false stereophony of the no-input material, the world forced into stereo because we’re biologically stereophonic; the Anthropocene, rising sea levels that will wash away the coastal cave painting of the crucifixion; the Son of Man as the poster boy for the Anthropocene, the human-shaped fulcrum of the Western calendar, the human face projected onto the Universe, the symbol of the dualism that artificially sets humanity and nature into opposition.

It also takes a few swipes at field recording clichés. The arms race to capture the most exotic location turned into that old Anne Rice piss-take: every vampire claims to have been present at the crucifixion. The pathological need to show a ‘whole process’ in sound, interminable bloody durations, yet here’s the process by which climate change erases a location in three and a half minutes via a business card CD-r that can only hold five minutes at most. And the location being intermittently accessible via tidal causeway, and you can’t hear it anyway, so did I bother going there, and if I did go there did I bother recording it, and if I did record it is it what you’re hearing?

Then there’s the Santa Barbara Christian Field Recording Association. From my Notes on Sightseer:

“I invented the SBCFRA at my Dad’s sixtieth birthday party on Hendry’s Beach in Santa Barbara. I was explaining my recording practices to Dad’s Charismatic Christian friends, three of whom were former session musicians with over a hundred years’ worth of recording experience between them… the hapless phonographers who make up the Santa Barbara Christian Field Recording Association are currently feuding in a denominational split between those who seek to record the Glory of God in His Creation versus those who are intent on capturing His Shekinah Glory as He fills the Tabernacle. While I spent a while toying with the idea of releasing a compilation album documenting the work of the collective, in the end I decided that Talibam! are a cautionary tale.”

I was once told about an encounter between James Dean Bradfield of the Manic Street Preachers and the English worship leader Martin Smith at a record label Christmas party, in which the former expressed utter disbelief at the amount of records the latter sold in the US. The notion of a shadow Christian field recording scene makes me laugh in a way that the gargantuan shadow Christian music industry doesn’t. I couldn’t get away from this stuff now if I tried – ‘The Trump Prophecy’ just got launched in 1,000 cinemas but will probably have a longer tail digitally, with white Evangelical support at an all-time high; my wife works in PR for a major loudspeaker company, a lot of sound engineers came up through the Evangelical scene and the company has resources dedicated to American superchurches; and a good chunk of her family live in Accra, where the exported American superchurch and prosperity ministry models are playing out in really toxic ways.

Even in the UK, where this stuff is much more invisibilised, I used to regularly play drums at services for hundreds of people, occasionally thousands. I grew up in a church in which a youth pastor tried to exorcise epilepsy from a teenager, so when exorcists declare that they’ll be defending Brett Kavanaugh against hexes it’s depressingly familiar. In the USA these people are mobilised and influential. We’re about to see mass migration and resource destabilization on levels we’ve barely imagined, driven by climate change scenarios that pose an existential threat unless we can adapt and mitigate at a pace that’s probably impossible. Meanwhile most of these people are anti-science at a fundamental level. Many of them already believe they’re engaged in a spiritual war. What will they do when the weather turns biblical?

WNNS: What about other forms of spirituality – around nature, for example? Or even the meditative blankness (ego death?) of the no-input field recordings – all those waves of noise? Could they function as a kind of trigger for meditation – noise for mindfulness?

Phil Legard commented on the similarities between the no-input material and scrying methods or EVP collection. I have a lot of respect for the rigour that Layla and Phil apply to their work, how they approach ‘place’ via developing new and old techniques and how that gets folded into culture, history, ideas, relationships. Their stuff is very timely. I’m happy to keep those ideas in the subtext, for now. I haven’t developed it but I’m not adverse to the idea in future. I just recognise that it will take a good deal of figuring out to make it into something that’s operable in a manner that fits with my principles and practice. K-Space is probably the best prototype – I have a lot of time for what Chamzyryn, Hodgkinson and Hyder achieved in that band.

My original response to this question was a lot longer… it’s something I’ve thought about a lot, particularly in terms of pitfalls to avoid, but I’m not about to approach it unless I’m absolutely sure it’s worthwhile and workable. Ask me again in five years! In terms of altering states, I used to use no-input recordings to send my youngest daughter to sleep when she was a baby. That’s enough for now.

8. It is finished

WNNS: I’m always interested in hearing artists talk about how they address starting and ending pieces of work. Does your process-based approach allow for fixed start and end points? In other words – to misquote Brian Eno – how do you know when you’ve finished?

SC: I often enforce a pause before signing off on a work. In the case of ‘Double B’ that was a 24-hour grace period, to allow for anything else coming to my attention and to review the latest iteration with fresh ears. Deferring for a day actually led to three major revisions. At the end of the first iteration I switched off the disc, switched on the radio and heard that permission for an alt-right conference involving Richard Spencer had been refused at Kent State University on 4th May 2018 (which they knew would happen from the outset – it’s yet another example of the vertical integration of fake free speech outrage, a tactic to supply your own controversy).

I used the coincidence to flesh out those components of the subtext. At the end of the second iteration I switch off the disc, switched on the radio, and found myself listening to Brendan Cox in interview. The album already contained a couple of references to Jo Cox, but I paused completion again so that I could audit the release to be sure it did what I needed.

And at the end of the third iteration I idly Googled ‘Mike Nelson’ for the first time in ages and found out that he would be present at an exhibition preview in Walsall the following day; en-route to that preview I listened to the news commentary about the Darren Osborne court case, which led to the inclusion of the tulpamancy 4chan material. And while incorporating that, the Jacob Rees-Mogg confrontation took place at the University of the West of England, along with Paul Golding’s retaliatory video message to “stay away from politicians on the right of politics.” So all that got incorporated too.

All the material had to be threaded through the record in ways that honoured the sculptors, particularly Mike Nelson, who is known for his large-scale works that layer narrative into interior spaces. A lot of his work involves sleight-of-hand or implied presence, and I adapted his building strategies into musical strategies. Things like repeating rooms, or incorporating his own workshop, or cannibalising material from one installation to make another. At the same time, I didn’t want the record to overbalance – it had to stay visceral and immediate. That was vital for me, because I needed that energy to purge some of that post-Brexit trauma. But I also wanted it to stand alone musically for the audience, for the conceptual and referential aspects to be optional for those willing and able to dig deep. I knew that the record was complete once it had achieved all the above, and once the final 24-hour pause-before-transmission passed without event.

It’s an odd week to be reviewing this paragraph, what with the pipe bombs sent to figures critical of Trump and the target images on the suspect’s stickered vehicle. Pausing before transmission isn’t about ensuring that a work is topical, it’s about taking a moment to ensure that the piece has its own internal life. Ongoing topicality is a side effect of getting this particular record right, other records live in different ways, and of course I’d prefer ‘Double B’ to talk about a time that we’ve since moved past.

Sometimes I’ll have a schematic. ‘Triangular Trade’ is a good example – I used a 3 x 3 thematic grid of 9 squares, in which I positioned all my various sound materials (instrumentation, borrowed audio, no-input field recording, processes etc.), adding material until every thematic possibility had adequate musical coverage. The piece is templated on John Akomfrah’s ‘Vertigo Sea’, so the overall duration was set from the outset, alongside a couple of marker-post events within that. I needed enough sonic components to fill that duration, but I also needed the duration to represent something much larger.

I had in mind that Smithson quote, “Size determines an object, but scale determines art. A crack in the wall if viewed in terms of scale, not size, could be called the Grand Canyon. A room could be made to take on the immensity of the solar system. Scale depends on one’s capacity to be conscious of the actualities of perception. When one refuses to release scale from size, one is left with an object or language that appears to be certain. Scale operates by uncertainty.” I’m generally dubious about long durations in music. So ‘Triangular Trade’ had to feel like centuries while lasting only 45 minutes, and perhaps counter-intuitively that required fewer sonic elements and events, held in tension over longer periods. I knew I had finished when I could account for all of the above, with the right sense of multidimensionality behind the sound and the right impact in the right places.

All the above hints at another thing I chase after – a sense that an album is ‘spinning’, which feels like the right word to me but might come across as a bit oblique. I know that a work is ‘alive’ when it feels as though it’s in perpetual motion, that it will either throw me back out into the world or suck me in, as though centrifugally or centripetally, if I try to approach it. I want to feel slightly dizzy listening to it and thinking about it. There’s also that narrative sense of spinning a yarn; imparting a bias either to throw a curve ball or spin a story; the forming of fibres into cord or shaping metal on a lathe. Spinning in a CD player (not on a turntable, because vinyl is shit). Once I achieve that, the work feels animated, and I can relate to it rather than merely own every aspect of it.

With some artists I get the sense that they’re megalomaniacs, with every possible angle mapped and understood, but that’s not what I’m after. I don’t want to be able to understand it all, to be able to hold it all in my head, because otherwise there’s no point in making it. Sometimes I achieve that through music alone, at other times the music is one part of a work that is also conceptual, maybe with a text component, or maybe it comes through the album art. Every release gets framed on its own terms – either with next to nothing, like ‘egregore’, ‘5102’ or ‘Four No-Input Field Recordings’, or with nine sheets of text collage and a hip-hop mixtape like ‘Triangular Trade.’ Sometimes it’s all music; sometimes it’s not music at all.

Lastly on ‘finishing’. I’m influenced by people I know far more than records I listen to. I’ve internalized a few of their voices when they’ve given me decent, robust criticism. These days I don’t seek feedback, partly because I can hear those voices, and if there’s slippage between the originator and my internal representation then that’s just part of me developing what I want to say. Plus I don’t always obey their voices like I do Batman.

WNNS: Conversely, how do you know when you’ve started? Do you have a list of areas to explore or do you wait for things to bubble up?

SC: I keep lists of titles, documents with ideas, empty file structures, objects that hold some kind of charge. Sometimes those things will hang around for years before they’re taken up in earnest, or sometimes I need to make something in order to figure out how I can make something else.

With a full-time job and a young family, if I allowed myself to get annoyed with delay or interruption I’d just be angry all the time. I use that lack of time. If an idea is good then it will stick with me, and I’ll return to it to discover that I’ve been developing it while doing other things. The two projects I’m about to embark on have been stewing for the better part of five years, and I finally know how to approach them.

+++

Biography: http://www.sethcooke.eu/info/

Discography: http://www.sethcooke.eu/

Every Contact Leaves A Trace label: http://www.everycontactleavesatrace.net/

Bang The Bore webzine: http://www.bangthebore.org/

+++

5 Comments